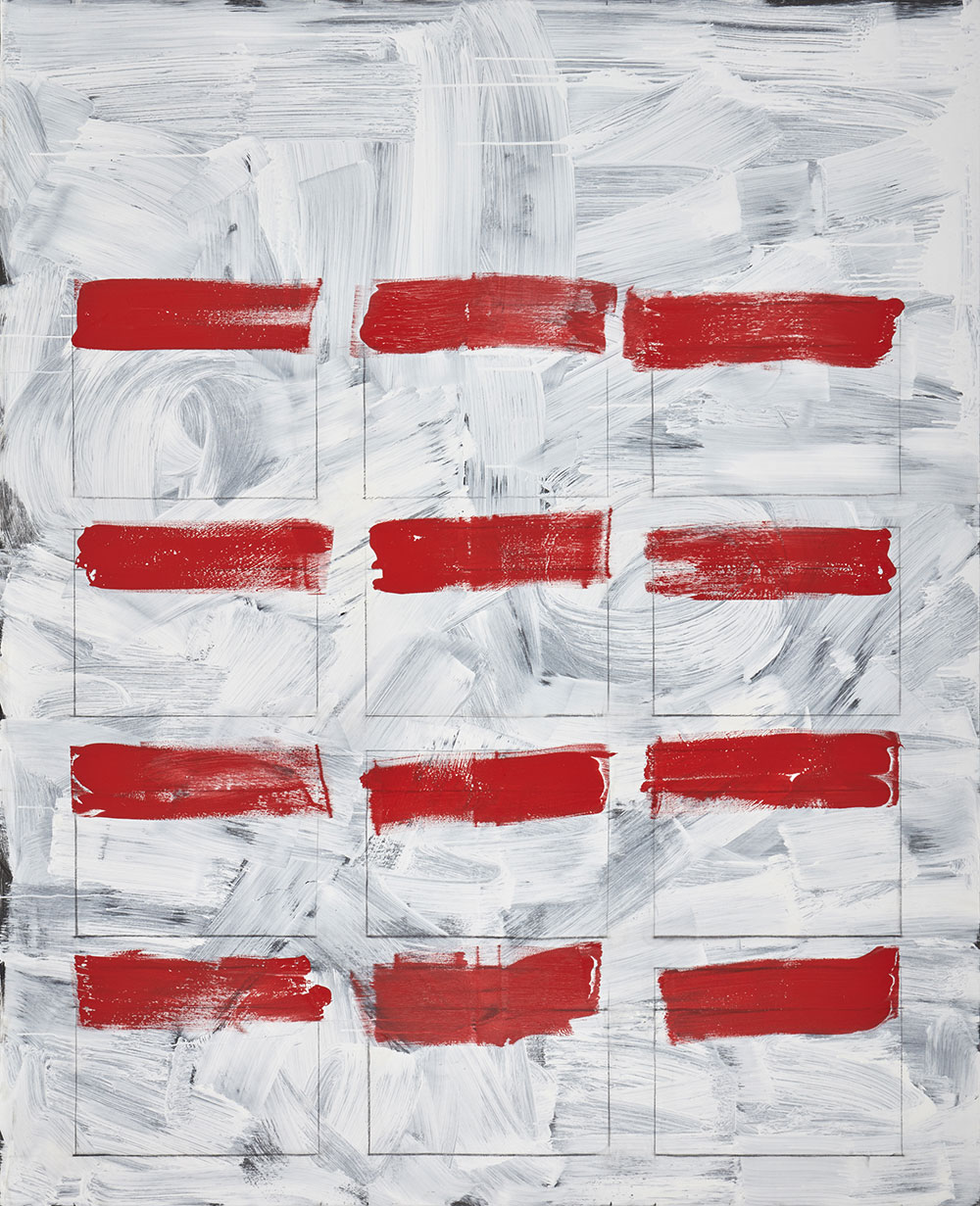

Days #1 (yearbook), 2019

Acrylic on canvas 250cm X 200cm

Days #3, 2019

Acrylic on canvas, 167cm x 250cm

Days #5, 2019

Acrylic on canvas, 200cm x 150cm

Days #7, 2019

Acrylic on canvas, 200cm x 250cm

Strange days #9, 2019

Acrylic on canvas, 200cm x 250cm

Days #12, 2019

Acrylic on canvas, 200cm x 250cm

Days #15, 2019

Acrylic on canvas and mirror steel, 250cm x 200cm

Days #17, 2019

Acrylic on canvas and a steering wheel, 200cm x 250cm

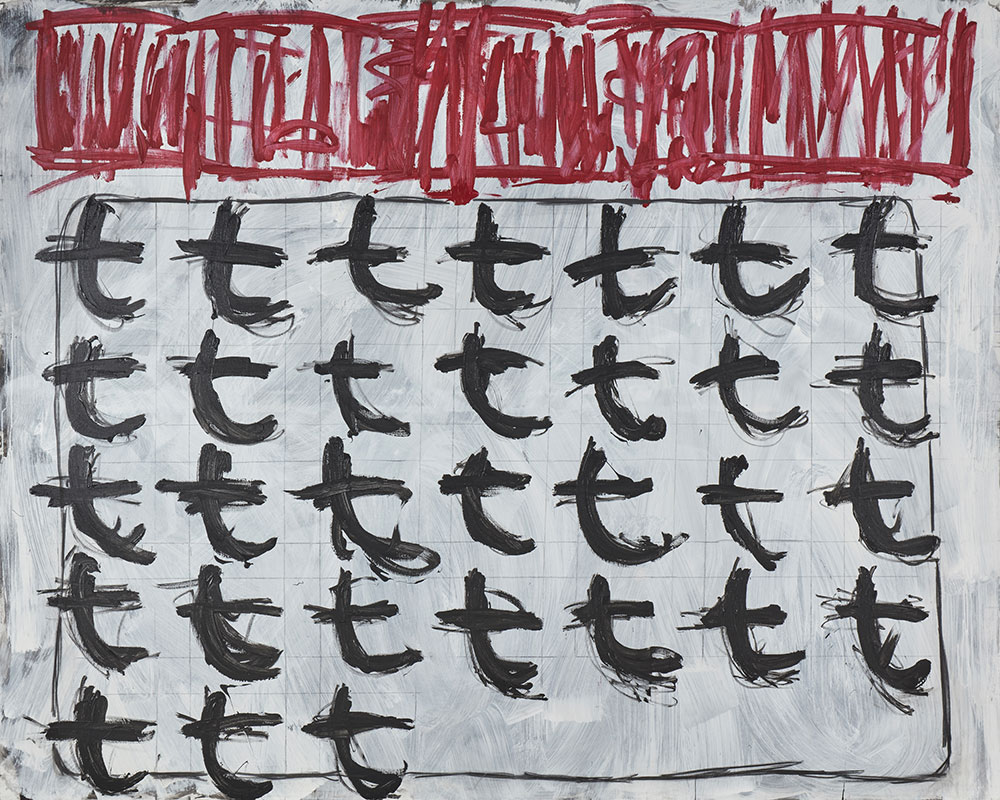

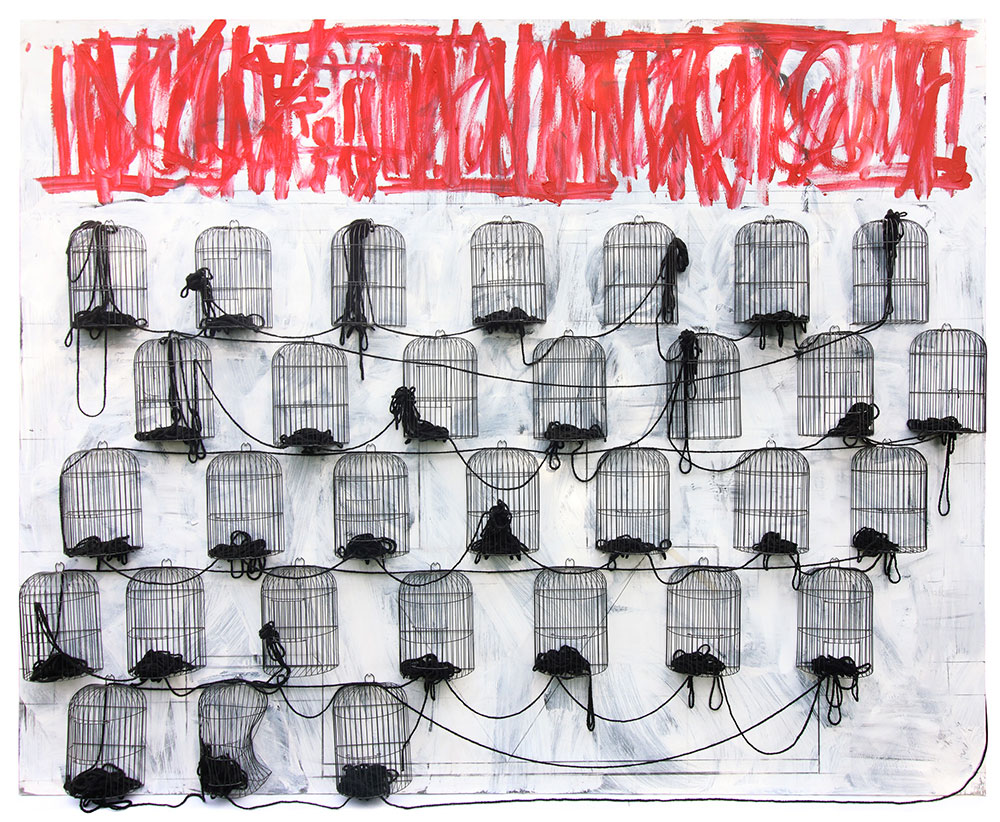

Days #18, 2019

Acrylic on canvas with metal cages and wool, 200cm x 250cm

TIME’S OUT (OR IS IT?)

With the street savvy and zest of graffiti, and a quirky neo-conceptual flair, Steven Fridman’s DAYS series of paintings (2018-2020) spurs the viewer on to a realization that time waits for no one (The Rolling Stones dixit, 1975), while triggering awareness of printed calendars as items (material culture) still to be seen all around, in homes, workshops and offices. DAYS explores the thematization of time. The simultaneous viewing of all the works in the series generates an odd kind of tension. Time just does not flow or pass in the exhibit; it remains literally present, laying siege to visitors. With a sort of ‘what you see is what you get’ cheekiness, too.

Few things in modern western homes are more familiar and banal than wall calendars composed of twelve tear-off sheets of paper printed with a regular lay-out of numbers and letters. Taken altogether, the twelve pages are an ancient conventional arrangement of the annual count of 365 days (366 on leap years), distributed in twelve different months, of a maximum of 31 and a minimum of 28 days.

The name of the month is always at the top of a page. Beneath it it, the distribution of numbers conventionally conforms to a lay-out of five rows by seven columns. A row of seven distinct ciphers in numerical progression from left to right corresponds to a week. Every column is organized under a letter allusive to the name of each day of the week, also in succession from left to right.

A wall calendar certainly is a good candidate for most ubiquitous, albeit unattractive and trite, slate of time-reckoning explicitly in print. Days can be ticked-off or crossed out in the expectation of the next; specific numbers in particular columns can be encircled as reminders of dates and appointments; holidays can be blocked-off as small chunks that visually stand for yearly leisure. Personal intentions and deadlines can also be expressed through markings of all sorts. Though it may be thought of as outmoded in this digital age, it still may carry facts, plans and dreams in short-hand.

The visual representation of time constrains the notion one may have of its passing. A wall calendar page literally is a grid-like representation of it. Steven Fridman resorts to making each canvas into a calendar page. DAYS, as a series, progresses from flat surface works in an abstract mode, to assemblage and installation work. Taking as his starting point the sameness of calendar pages, he places next to one another paintings that are not quite repeats of each other to induce a displacement of the reading frame. Calendar pages may differ in number of days per month, colour schemes, name abbreviations, typographic fonts and font size. We are so familiar with all these differences that we don’t notice them. By the same token, in Fridman’s works, viewers are invited to compare and contrast for themselves.

The artist eliminates and/or substracts explicit information that by convention is part of the basic design. There are no names of months or days, in full or in abbreviation in any of the works. The abstract mode imposes itself on the borrowed motif. The color scheme provides an abstract structure throughout, amounting to a red, thin shape, suggesting a rectangular form fleshed out through scribbles, doodles, overwritings and obliterations; and beneath it a rectangular body of expressively handled white paint over a black ground, that extends to the edge of the canvas. It is on this painted field that other signs are added, all of them seem to be abstract. Some are vernacular, commonplace markings; others are scientific symbols or mock-erudite, pseudo-calligraphic notations. The similarity in basic composition of all canvasses suffices for a system to be generated. This underlines the neo-conceptual edge of DAYS as a series. The dismantling of the referent allows the configuration of a possible new visual metaphor. (This does not exclude a possible metonymical reading of the series).

Painting as a contemporary aesthetic practice reverberates and becomes actualized in the works through possible readings in art-historical terms. Damien Hirst’s multi-coloured spot paintings of the 1980s referenced Gerhard Richter’ color scheme paintings (Farbtafeln) of the mid 1960s. In the process, rectangles became discs. Fridman prefers black dots. The strict colour range maintained throughout suits his proposal. The black dots in matrix–like arrangement stimulate a soft-pulse optical effect: marks on the surface beat per sectors, alternately keeping time as vision roams the painted surface.

The assemblages offer a different line of enquiry in the exploration of time as a theme in painting. The affixing of material objects to the surface of the canvas adds a distinct layer of materiality that accrues symbolic density and dimension, and unleashes mental energy generously. The recognition of self is brought to the fore in assemblage-paintings in which Fridman incorporates mirrors. The canvas has been suggested to stand as a reflecting plane held up to the artist´s bodily presence with painting embodying narcissistic impulses. The transient nature of reflections in mirrors affixed to the canvas surface is underpinned by the classical myth of Narcissus and brings impermanence into the equation. The individual viewer briefly stands in the artist’s shoes. Viewers, however, may choose to only recognize their fleeting reflections as part of the work’s symbolic net. Thus, they ssee themselves interacting with the asssemblage and through their reflected bodies are briefly integrated to it.

Another assemblage galvanizes the conceptual programme: being tethered to time is articulated at this point in the series as captivity in relation to the pictorial surface, with an evident, concrete sign materialized in the ball and chain that weighs down on the body in forced labour in a prison yard. Bitterness and irony go hand in hand. Movement is hampered both by the weight of the ball’s mass as well as by the chain that emerges from the painted canvas to set a new degree of interference with viewers. This work invades viewers’ space in direct relation to the number of floor elements. The assemblage, thus, veers to installation.

After the COVID 19 pandemic started and lockdown ensued almost everywhere, a ‘meme’ was extensively shared among those suffering the disconcerting real-life experience of confinement in the home, advocated by health authorities universally. The text of the ‘meme’ reads:

UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE THE DAYS OF THE WEEK ARE NOW CALLED, THISDAY, THATDAY, OTHERDAY, SOMEDAY, YESTERDAY, TODAY AND NEXTDAY!

Is time stagnating, lately? More likely, time is passing unheeded since undifferentiated, as routines fade away or slacken. Unusually so. We stay home and work, or attend school or university, consult with doctors or lawyers and shop from there, thanks to our computers, tablets and cell phones. Unless we are strict, our working hours tend to overrun our leisure time.

DAYS confronts us in this time of transition. Without caveats, carpe diems or moral imperatives. Just art as necessary re-enactment of faith-keeping, in the midst of our doubts and fears, when we are at a loss for words.

Jorge Villacorta

Curator